by Gustavo Dudamel and Anita Walker

Look and listen closely to the student ensemble from Boston String Academy and you experience something profound. You hear music, of course: works from the classical repertoire played at extraordinarily high levels. You see learning too—rapt attention, mathematical precision, deft coordination. Peer more deeply and there’s still more: creativity, connection, community.

This is the power of the ensemble under the El-Sistema-inspired model of music education. Led by highly trained, caring teachers, a rich curriculum, and challenging opportunities for public performance, Boston String Academy students and thousands like them across Massachusetts are redefining what art means to young people, particularly those struggling against poverty and other socioeconomic barriers. They come to understand themselves not only as musicians and performers, but as citizens who matter and can make a difference in their community. This model of learning transcends music and is being adopted in the visual arts, theater, history, and science. It’s called creative youth development and it is drawing attention from educators and policymakers across the nation.

We have come to be champions for creative youth development from very different places: One of us was steeped in El-Sistema from childhood, under its founder and his mentor, Maestro Jose Antonio Abreu, who later initiated a ground-breaking cooperation between El Sistema in Venezuela and the New England Conservatory. The other saw El Sistema’s power on visits to South America and other US cities with NEC, then undertook to plant its seeds more deeply and broadly here in Massachusetts.

Those seeds continue to blossom. Mass Cultural Council now supports more than 22 El-Sistema inspired music programs across the Commonwealth through its SerHacer Initiative—from Lawrence Public Schools’ first-even string orchestra, to Kids 4 Harmony, grounded in a social service agency called Berkshire Children and Families that serves some of that region’s most vulnerable youth. At the same time the Council continues a decades-long investment in dozens of creative youth development initiatives that reach youth through other disciplines—from The Care Center in Holyoke, where history and literature open teen mothers to new ideas and new life possibilities, to Provincetown Art Association and Museum’s ArtReach, where teens learn about themselves and the world around them through drawing, painting, and digital artmaking.

On April 8, we joined state legislators, philanthropic and civic organizations, and cultural leaders at WBUR’s new CitySpace to honor these efforts and others with the 2019 Commonwealth Awards, Massachusetts’ highest honors in the arts and culture. These Awards remind us that even amidst our highly politicized and polarized world, art and music unite us. Leonard Bernstein, our great native son whose centennial we just celebrated, put it this way: “It is the artists of the world, the feelers and the thinkers who will ultimately save us; who can articulate, educate, defy, insist, sing and shout the big dreams.” It is true: everyone who contributes to the creation of beauty in this world helps carve out the vital time and space for people of all walks of life, all cultures and diverse political views to dream together. That is the power of music. And we need music today more than ever.”

Massachusetts was not just the birthplace of the American Revolution, it is also at the heart of this nation’s cultural revolution. This state is renowned for creating and fostering some of the most esteemed institutions – both large and small – in the arts and education. And from such institutions come ideas and creative experiences that make people talk, think, and feel. The people and organizations of Massachusetts have brought joy and passion to millions of people, and helped fundamentally shift the paradigms of our social, intellectual and artistic understanding.

Let’s make sure we continue listening to each other and working together to foster a world that cultivates, embraces and empowers the arts. A world without them is unacceptable – and unimaginable.

Gustavo Dudamel is Music Director of Venezuela’s Simón Bolívar Symphony Orchestra & Music & Artistic Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

Anita Walker is Executive Director of the Mass Cultural Council, a state agency supporting the arts, humanities, and sciences.

Mass Cultural Council’s SerHacer program is supported by the Dudamel Foundation.

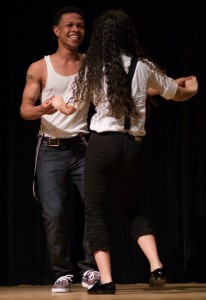

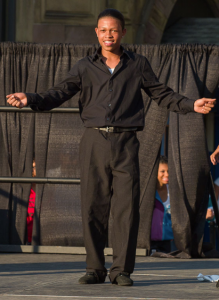

I arrived in Boston from the Dominican Republic when I was 13. No one told me I was going to a new country until the day before I left. When I got to Boston, I lived with my grandmother in a housing project in South Boston. I remember it was the end of November, and I didn’t have any warm clothes. I didn’t speak a word of English.

I arrived in Boston from the Dominican Republic when I was 13. No one told me I was going to a new country until the day before I left. When I got to Boston, I lived with my grandmother in a housing project in South Boston. I remember it was the end of November, and I didn’t have any warm clothes. I didn’t speak a word of English.